Mangile’s Pigeon Pages

Taken from the Chicago Tribune

October 7, 1900 - page 38

October 7, 1900 - page 38

LIVES AMONG 500 PIGEONS.

Important Experiments by Prof. Whitman of University of Chicago.

With 500 birds as his companions and subjects

Professor Charles O. Whitman of the University of Chicago has for six

years been studying and conducting experiments which before long it is

promised will give results of the utmost scientific value and which

will pass even for the layman far beyond the bounds of the merely

interesting.

With 500 birds as his companions and subjects

Professor Charles O. Whitman of the University of Chicago has for six

years been studying and conducting experiments which before long it is

promised will give results of the utmost scientific value and which

will pass even for the layman far beyond the bounds of the merely

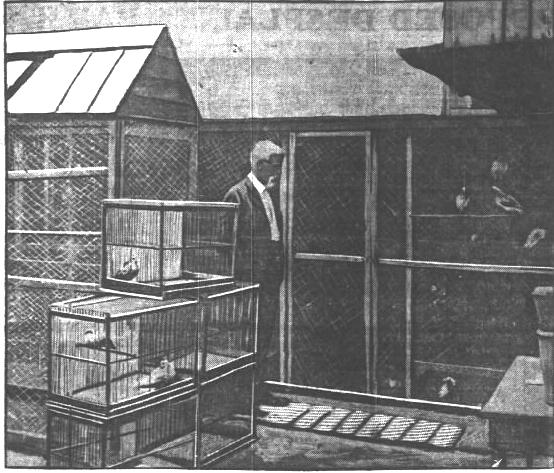

interesting.Every person who passes by the handsome stone residence, 223 East Fifth-fourth street, and who lets his eyes rise above the level of the steps, is struck by the sight of scores of pigeons brushing their burnished feathers against the glass of the bay windows which form the outer side of the great cages in which they are confined. The residence is the home of Professor Whitman, who is making the pigeon tribe a study, and who, in order to do the work more thoroughly, literally lives with his subjects.

Professor Whitman has not only made home companions of half a thousand wild and domestic doves, but, in order that he might not have his studies interrupted, they have been his traveling companions as well. Last week, in the house of the student and in the grounds at the rear, there was enacted a scene of the most intense interest to all scientists who have made animal intelligence a study. Cages containing the 500 pigeons had their doors opened wide and the birds set at liberty. They have just been brought back from the three months stay at Wood’s Hole, Mass., where Professor Whitman had pursued his summer bird studies. Upon the opening of the door of its cage each pigeon unerringly made its way instantly to the particular cote which it had occupied before leaving Chicago for its summer outing by the sea. Nine months hence, when the birds are taken back to Wood’s Hole they will be turned loose again and each will fly at once to the cage where it passed the summer which has just waned to autumn.

Studying Laws of Heredity.

Professor Charles O. Whitman is a believer in the theory that the study of the habits, instincts, and intelligence of the lower animals has a fundamental relation to the study of man’s menial development. He is devoting himself closely to minute investigation of the laws of heredity and all the correlated phenomena that springs there-from. This quiet university scholar who literally has pigeons at his bed board and books has succeeded in his South Side home in securing some of the most remarkable results from cross-breeding experiments known to the pigeon fancying world. He has in his collection, or, perhaps as he would prefer it, among his companions, representatives of perhaps every know kind of pigeon that the world produces. Further this he has with the sole exception of a few birds owned in Milwaukee, the only known living specimens of the American passenger, or wild-pigeon, now extinct in the wild state, but which only a comparatively few years ago was the most widely distributed and numerous of American birds.

All Kinds of Pigeons.

Within the scope of the collection Professor Whitman has pigeons which in size are no larger than a sparrow, and others, the crowned pigeons of Australia, whose bulk is as great as that of the bald eagle. There are in some of the cages which hide the walls of the student’s library featherless little-creatures just out of the shell which claim for parents mothers and fathers of two totally different pigeon tribes, and of such extremes in size that the one parent in some instances would easily make three of the other in weight, length, and breadth of wing. One curious feature of the collection is the sight of some hard working ring doves feeding, cuddling, and doing their best to bring up in the way they should to young ones which have no natural claim on them whatsoever, before the offspring of some pair in an adjoining cage who lack either the inclination or the ability to bring up children properly.

It might be supposed, possibly, that Professor Whitman chose pigeons as a study because of their superior intelligence. As a matter of fact the birds are less intelligent than many of their feathered brothers of other families, and they were chosen for study because of their adaptability to conditions of confinement, but more particularly because the great number of varieties in the family gave an unlimited field for crossing experiments and resulting observations on the effects of heredity. If a person wishes to use a perfect example of reversion or atavism Professor Whitman will show him a pigeon of which every feather is as white as a spring snowdrop, while its parents in the next cage are the one as black as a nun’s hood and the other as gray as a foggy dawn. One of the grandparents of this bird was white and the coloring of a grandchild simply shows reversion to a former type.

Touching the reason for his keeping in such close contact with the subjects of his study, Professor Whitman says this: “The life history of animals from the primordial germ cell to the end of the life cycle; their daily periodical, and seasonal routines; their habits, instincts, intelligence, and peculiarities of behavior under varying conditions; their geographical distribution; their physiological activities individually and collectively; their variations, adaptations, breeding and crossing – in short, biology of animals, is beginning to take its place beside the more strictly morphological studies which have so long monopolized the attention of naturalists. The essentials to understanding any peculiar case of animal behavior are almost invariably overlooked by inexperienced observers, and the best trained biologist is liable to the same oversight, especially if the habits of the animal are not familiar. The qualifications absolutely indispensable to reliable diagnosis of an animal’s conduct is an intimate acquaintance with the creature’s normal life, its habits and instincts. Little can be expected in this most important field of comparative psychology until investigators realize that such qualification is not furnished by parlor psychology. It means nothing less than years of close study – the long continued, patient observation, experiment, and reflection, best exemplified in Darwin’s work.”

Cause of Tumbling Habit.

Pigeon fanciers and thousands of other people as well, for that matter, have always been puzzled to account for the origin of the instinct of tumbling, a habit which a certain breed of the birds indulges in constantly, and which makes of the tumblers a special prized class. Through his long study of the pigeons, both caged and at liberty, Professor Whitman has arrived at a certain conclusions touching this tumbling practice, which are as interesting as they are new. He says that the probably source of the origin of tumbling was undoubtedly a general action instinctively performed by the ordinary dovecote pigeon.

“I have noticed a great many times,” said Professor Whitman, “that common pigeons when on the point of being overtaken and seized by a hawk suddenly flirt themselves directly downward in a manner suggestive of tumbling and thus elude the hawk’s swoop. The hawk is carried on by its momentum and often gives up the chase on the first failure. In one case I saw the chase renewed three times and eluded with success each time. The pigeon was a white dovecote bird with a trace of fantail blood. I saw this pigeon repeatedly pursued by a swift hawk during one winter and it invariably escaped in the same way. I have seen the same performance in other dovecote pigeons under similar circumstances.

“But this is not all. It is well known that dovecote pigeons delight in quite extended daily flights, circling about their home. I once raised two pairs of these birds by hand in a place several miles from any other pigeons. Soon after they were able to fly about they began these flights, usually in the morning. I frequently saw one or more of the flock while in the middle of a high flight and sweeping along swiftly, suddenly plunge downward, often zigzaging with a quick helter-skelter flirting of the wings. The behavior often looked like play, and probably it was that in most cases. I incline to think, however, that it was sometimes prompted by some degree of alarm. In such flights the birds would frequently get separated and one thus falling behind would hasten its flight to the utmost speed in order to overtake its companions. Under such circumstances they stray bird coming from the rear might be mistaken for a moment for a hawk in pursuit and one or more of the birds about to be overtaken would be thus induced to resort to the tumbling method of throwing themselves out of reach of danger. The same act is often performed at the start as the pigeon leaves its stand. The movement is so quick and crazy in the aimlessness that the bird often seems to be in danger of dashing against the ground, but it always clears every object. As this act is performed by young and old alike, and by young birds that have never learned it by example, it must be regarded as instinctive and I venture to say that is probably represents the foundation of the more highly developed tumbling instinct.”

Pouting Due to Heredity.

The instinct of pouting among pigeons has received a large share of Professor Whitman’s attention, as it likewise did that of Darwin. “Darwin,” said Professor Whitman, “saw at once from the nature of the actions that they could not have been taught, but must have appeared naturally, to use his own words, through probably afterwards vastly improved by the continued selection of those birds which showed the strongest propensity. Darwin then postulates as the foundation of each instinct a propensity - that is, something given in the constitution. This view of the matter is quite incompatible with the habit theory, though in entire account with the theory adopted in the case of the neuter insects.

“I believe the case is much stronger than Darwin suspected and that the pouting shows not the genesis of instinct from habit, but from a preexisting congenital basis. Such a basis of the pouting instinct exists in every dovecote pigeon and is already an organized instinct, differing from that displayed in the typical pouter only in degree. I could show that the same instinct is almost universal among pigeons. Just let me call attention to the instinct as exhibited in common pigeons. Look at the male pigeon while cooing to his mate or his neighbors. He inflates his throat and crop, and this feature is invariably shown in the act of cooing and often continues for some moments after the cooing ceases. Compare the pouter with the common pigeon and notice how he increases the inflation whenever he begins cooing. The pouter’s behavior is nothing but the universal instinct enormously exaggerated as any attentive observer may readily discover for himself under favorable circumstances.”

Explains Alleged Insanity.

Romanes, the scientist, in his “Mental Evolution of Animals,” gave wide publicity and the weight of his own authority to the story of a pigeon that went insane. One of the results of Professor Whitman’s investigation is a refutation of the Insanity theory of Romanes and the giving to the scientific world of some instances of more ‘insane” actions on the part of perfectly normal pigeons that those attributed to the supposedly crazy bird. The pigeon of Romanes was a white fantail, which became, as the original report went, the victim of a peculiar infatuation. The story goes: “No eccentricity whatever was remarked in the pigeon'’ conduct until one day I chanced to pick up a ginger beer bottle of the ordinary brownstone description. I flung it into the yard, where it fell immediately below the pigeon-house. That instant down flew pater famillas, and to my no small astonishment commenced a series of genuflections, evidently doing homage to the bottle. He strutted round and round it, bowing and scraping and cooing and performing the most ludicrous antics I ever beheld on the part of an enamored pigeon. Nor did he cease these performances until we removed the bottle; and, which proved that this singular aberration of instinct had become a fixed delusion, whenever the bottle was placed or thrown in the yard the same ridiculous scene was enacted. The pigeon came flying down as quickly as when his dinner was thrown out, and he continued his antics as long as the bottle was allowed to remain. Sometimes this would go on for hours, all the other pigeons treating his movements with the most contemptuous indifference and taking no notice whatever of the bottle.”

Saw His Image Reflected.

Mr. Romanes believed that this pigeon was affected with a strong and persistent monomania, and said that, although it was well known that insanity was not an uncommon thing among animals, this was the only case he had met with of a conspicuous derangement of the instinctive as distinguished from the rational faculties. Professor Whitman had this case in mind during the course of his pigeon studies, and says plumply that this particular pigeon, whose behavior had given it so wide a fame as a lunatic, was undoubtedly a perfectly normal bird. ‘I have seen,” he said, “a white fantail play in the same way to a shadow on the floor, and when the shadow fell on a crust of bread he at once adopted the bread as the object of his affection and went through all the bowings and genuflexions ascribed to the “insane” bird, even to repeating the behavior every time I place the same piece of bread on the floor of his pen. The chances are that the “crazy” bird saw his shadow upon the bottle or his image faintly reflected on it surface.”

A large number of Professor Whitman’s pigeons are wild birds. The two crowned pigeons of Australia, the largest of the pigeon tribe, go fluttering with fear at the approach of any one save him who feeds and owns them. In a cage just beyond is a naturalized Filipino pigeon, perhaps the most beautiful of all the many varieties that go to make up the family. This bird is called the “bleeding heart” because of the brilliant red splash upon the whiteness of the breast. At a little distance it looks as though the birds was wearing a damask rosebud. There are pigeons from China, from Africa, from South America, and practically from all known lands.

Experiments in Crossing.

In the crossing and recrossing of the different varieties which Professor Whitman has accomplished he is given the opportunity that he seeks to see which of the parent’s traits are the more strongly impressed upon the offspring. The professor has succeeded in crossing the American wild pigeon with several of the different relatives. The mourning dove, so common in Illinois utterly unlike it is appearance and characteristics. Among the most prized birds in the collection are some blue rocks, captured in the wild state on the coast of England. These birds of which there are few left in the sate of freedom, are the counterparts of the hardy blue rock, which for years has been domesticated and which is used on account of it strong flight at nearly all trap shooting contests. The domestic birds are the descendants of the wild blue rocks captured generations ago.

While Professor Whitman’s residence is today in large part given over to the occupancy of pigeons, within a few weeks almost all the available wall space in every room will be lined with cages, for the cold weather will necessitate the removal of several hundred additional birds to the warmth of indoor quarters,. As the professor put it: “Companions to the number of 500 might seem too many for comfort, but then their variety is infinite and their interest never lags.”

# # #